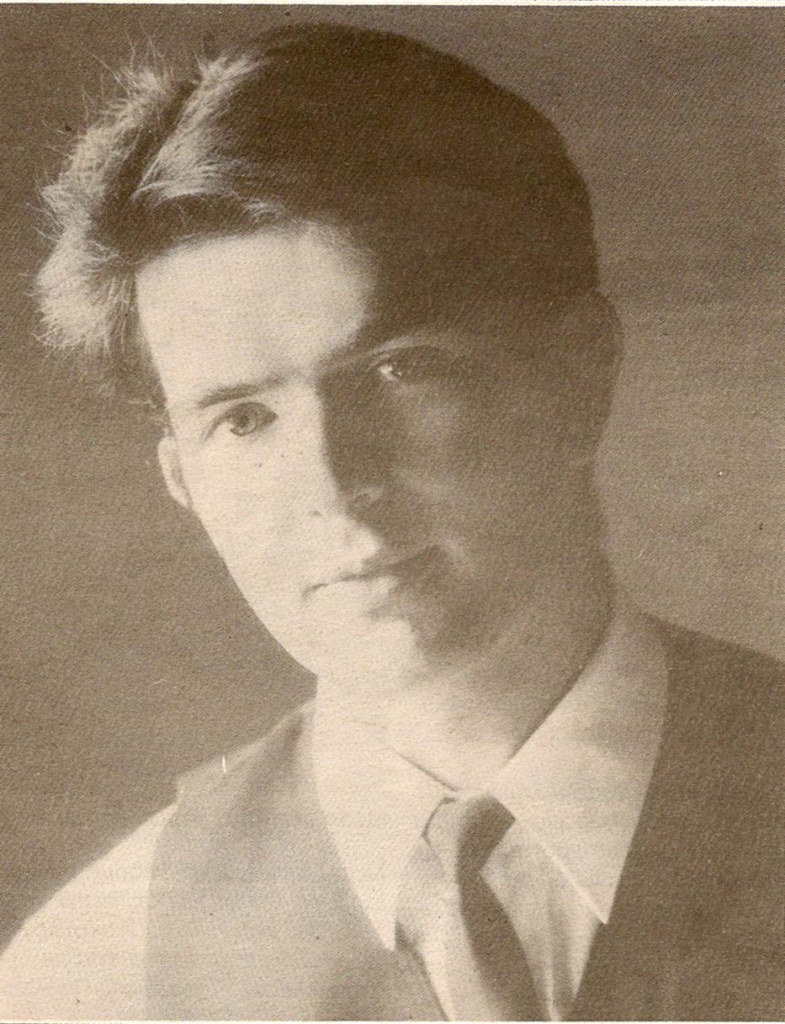

In this personal perspective, Cultural Infusion’s Founder and CEO Peter Mousaferiadis shares his experiences with racism as a child of migrants. This piece represents the first in a two-part series based on his talk at SIETAR Europa panel discussion on enhancing equality and countering discrimination, racism and intolerance: experiences.

Before I begin to respond to the question of how data can provide a framework to antiracism strategies, I’d like to take a few moments to provide you with my personal perspective and how it led to the work I am doing at Cultural Infusion.

Two decades ago when I founded Cultural Infusion, my goal was to create cultural harmony through intercultural action. Since then, we’ve gone on to develop further programs as society too changed – most recently, with a view to use data to provide a framework for antiracism strategies, we developed our flagship product Diversity Atlas.

This mapping tool helps organisations across the globe make their settings more equitable, representative and inclusive by providing comprehensive insights and personal perspective into the extent and type of cultural and demographic dimensions of diversity.

Early years

Whenever I think about the directions my life has taken, I have to circle back to when and where I was born. Melbourne’s western suburbs during the 1960s and 1970s was already a culturally diverse landscape. From a personal perspective, I remember being inspired even then, working in my parents’ milk bar in Newport.

Going back further, it is a little known fact that before Europeans colonised Australia in the late 1700s, there were an estimated 700 languages and speech communities. These represented 324 distinct ethnic groups or nation states.

Australia Day concerts

Back before Cultural Infusion, I spent a rewarding two decades as a composer, conductor and creative director – it was during this extensive career I had the opportunity to produce nine Australia Day concerts including countless international productions including Opening and Closing Ceremonies for a range of clients including the United Nations and Parliament of World Religions.

My final of the Australia Day concerts was in 2012. I was backstage with the most senior First Nations custodian of the City of Melbourne and the Wurrendjeri People, Joy Murphy.

Curious, I asked her:

“Joy, how many thousands of people speak Woiworrung, the language of your people?”

She was surprised.

“How many thousands? There is only one living person who speaks the language of my people. My Auntie,” she finished sadly.

Take a moment to imagine: how would you feel, being the last surviving speaker of your mother tongue?

700 languages and speech communities were spoken in Australia before European settlement. Today, only 15 of these are taught in Australia.

The decimation of languages, cultures and peoples in Australia is probably the greatest tragedy of our history.

White Australia Policy

We are a country born of racism. Looking at historical facts, this is undeniable – in 1901, we developed the Immigration Restriction Act as a precursor to the notorious White Australia Policy. On this policy, we based our entire allegedly multicultural identity.

I’d like to re-iterate: the White Australia Policy. The act that essentially allowed White Australians to discriminate without fear against anyone deemed different.

Things didn’t improve quickly thereafter – racism continues to be an omnipresent stain on our national identity. So, too, is the shameful act enshrined in policy until the 1970s, the act of confiscating First Nation children from their families. This became known as the Stolen Generation.

From my own personal perspective, I have known many people over the years subject to this inhumane procedure. This is trauma enough, but we compound it with our attempt to airbrush Australia free of Indigenous people. The impact continues through generations to today.

Australia’s Migration Wave

Every wave of migration that has flowed into Australia since 1901 has experienced ethnic and race-based discrimination.

Back in the 70s where I lived, people who had non-anglo names would usually change them. We’d say it was for ease of pronunciation – a pre-emptive defense against the very real chance our birth name would be weaponised and used against us.

At various times in my life, I have felt excluded from interviews because these same people who would have made fun of my name, did not think I was Australian enough – despite my Australia passport saying otherwise. From my personal perspective, I have never felt part of the status quo. Nevertheless, this drove me to find creative ways to pave a career in the arts.

I realised very quickly that producing large scale intercultural events was not enough. While these events celebrated the coming of people together, real change could only take place through education.

Education as The Answer

At Cultural Infusion and until Covid-19, we proudly delivered our education programs to more than 350,000 students annually. Our dedicated and diverse range of cultural presenters create authentic intercultural experiences.

Discrimination is driven by ignorance and fear. It then follows that the counter drivers are familiarisation and collaboration.

It is this thought that underpins everything we do at Cultural Infusion.

Racism still exists and I’m under no illusions it will go away overnight.

To eradicate racism, we are going to need a monumental – revolutionary even – paradigm shift in the way we think. Let me go as far a saying, perhaps an evolutionary shift in human cognitive development.

In reality, all societies resonate with a dimension of history and ingrained culture. Privileges are associated with a hegemony not afforded to anyone but the dominant group. Racism in the west, furthermore, can be traced back to a geo-politics of individualism and neo-liberalist ideas.

From a personal perspective, my work has shown me the need to use market forces to motivate behavioral change in regards to discrimination. We also need to better understand the drivers behind it.

To say ignorance is a driver of discrimination can also be worded: we don’t know enough or better still we don’t know what we don’t know. When we access data, however, we are afforded insights that facilitate a more thorough, informed decision-making process.

The first step we need to take is ensuring we aggregate better data on cultural diversity. This will ensure all practices, policies and programs are targeted and designed to close the inclusion and representation gap.

We don’t yet know the true extent of this opportunity to close the inclusion and representation gap for the very reason that reliable, consistent data in that area does not yet exist.

Effects of COVID-19

This pandemic wreaking havoc across the world has exacerbated and perpetuated inequality and difference by highlighting the following points:

• The conflation of race and ethnicity is perpetuating health inequality

• So, too, is our lack of data

• We need to take a nuanced approach to data.

COVID-19 has highlighted massive disparities between groups of people in respect to who is represented in our culture, and who is not. We have seen a relationship between health and ethnicity, and yet, we continue to use blanket-approaches. As yet, we are not taking into account socio-economic factors playing a role in community transmission of COVID-19.

Moving forward, it will become more important than ever to double down on incorporating diversity, inclusion and workplace equity in addition to ensuring that culturally responsive approaches are being implemented.

Share this Post