Last month I wrote a blog post “It’s About Time: A New Era of Diverse U.S. Leadership”, which celebrated the recently inaugurated Biden cabinet for being the most culturally diverse and gender inclusive in American history. Even as this overwhelmingly positive move was lauded as, yes, well past time, another question emerged: as an Australian, why not write about diversity in Australian politics?

It is with some reservations, this time, I will. Why did I not want to discuss this initially? Well, without wanting to divulge the answer up front let’s say it will become clear as you read on.

I should note, before we begin – in as much as I don’t like blanket descriptions such as ‘white’, ‘black’ ‘hispanic’ because of the disproportionate impact of clustering many cultures into one group, for the purpose of this post, I will keep it in theme with the previous one and expand on my reasons on a future post.

Some context: former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull has rather famously boasted Australia is the “most successful multicultural society in the world. There is no other country that has done so well at this as we have.”

We presume we are a country that champions diversity, and celebrates our differences while welcoming newcomers. We’re the country of the ‘fair go’, where anyone can rise to the top if they just work hard enough. We like this comforting narrative.

“Welcoming newcomers’ is debatable, and also worryingly controversial. Yes, our national anthem’s second verse includes this, however when we are detaining arrivals and isolating them on islands with harsh conditions for years on end I’d say is a little off welcoming.

“For those who’ve across the seas

We’ve boundless plains to share

With courage let us all combine

To advance Australia fair”

As such, these presumptions – nebulous and intangible – don’t hold up to scrutiny quite so well as this narrative we enjoy of Australia as a multicultural utopia would suggest. This is particularly obvious when we consider them in relation to the demographic makeup of our elected representatives in parliament.

Where we stand now

While it is true that Australia’s population is drawn from over 300 ancestries, with various generations of immigrants shaping our cultural landscape, it is difficult to ignore some inconvenient facts when sharing this piece of hyperbole. As Andrew Jakubowicz notes, the Australian political landscape is overwhelmingly populated with WACA – white, anglo-celtic Australians.

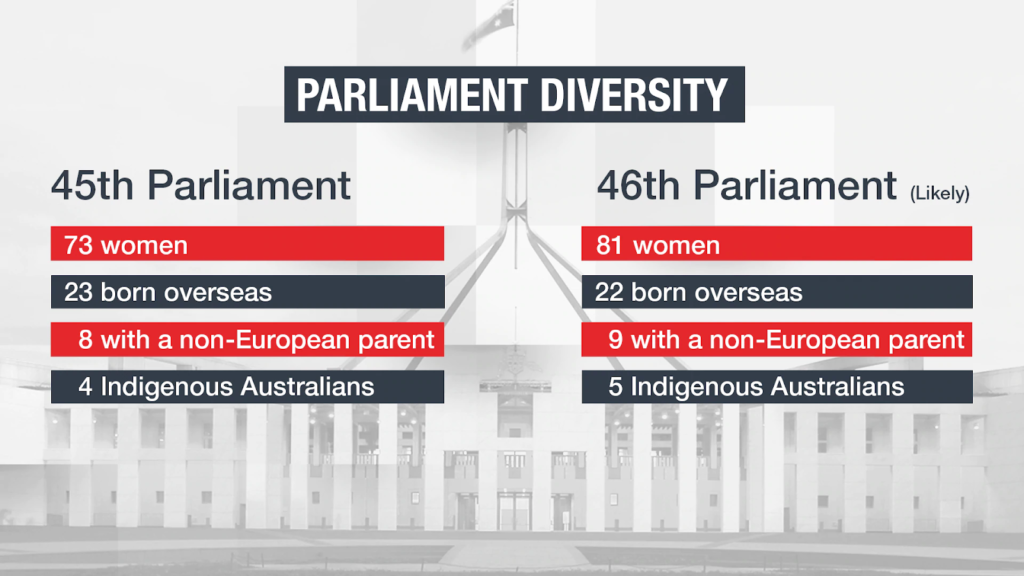

It is difficult, with a remarkably high turnover of political assignments, to get an entirely up to date and exact quantitative view on the cultural makeup of our parliament and high court. This in and of itself is a problem. Previous surveys suggest as high as 79% of the 226 elected politicians are of Anglo-Celtic Australian stock.

Women comprised only 37% of candidates running for election in 2019, less than 2% were of indigenous background and only 1% of any major party had a disability.

1 in 10 of candidates were from culturally diverse backgrounds.

All this, despite 33.2% of our population having been born overseas. Despite 27.3% of people speaking a language other than English at home.

Morrison’s 2019 Cabinet – Photo: Sydney Morning Herald

In the very highest echelons of government, there is even less diversity. There are 22 Cabinet members, in which there is one Aboriginal representative, Indigenous Affairs Representative Ken Wyatt. There are six women. The rest are men of European descent.

This lack of mutuality, or equal representation between the elected representatives and the communities they serve, is of concern. Simply put, the cultural makeup of the population of the Australian political system as an organisation is wildly out of step with the demographic makeup of the constituents they seek to represent.

In any organisation, this is of significant concern – representation of diversity matters. When that organisation’s sole responsibility is, ideally, the representation of the interests of their wider communities, it is distinctly worrying.

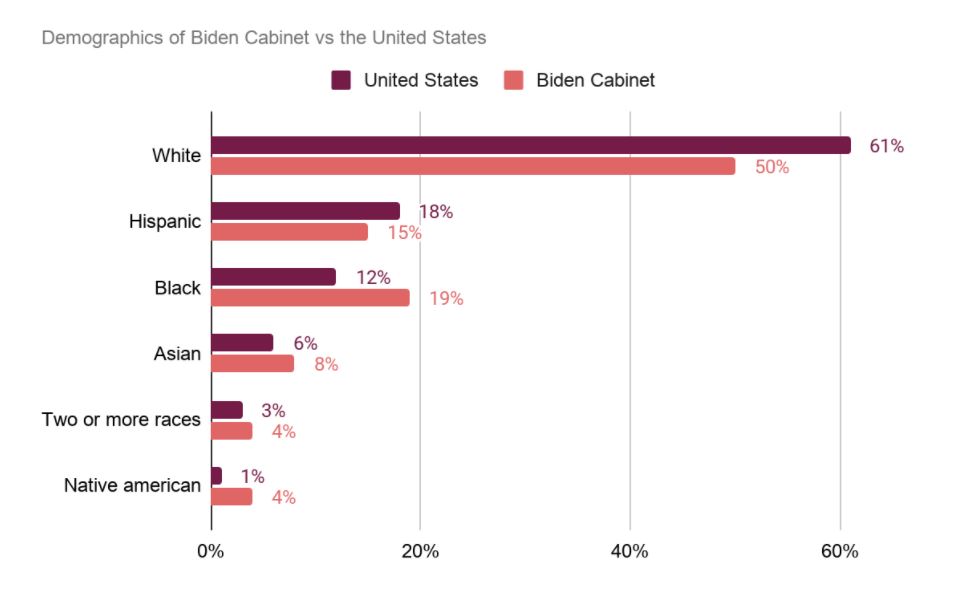

Let’s compare the data we have on Australian political diversity to the Biden administration’s, then make some direct comparisons:

Explicitly, 50% of Biden’s cabinet is ‘white’. In Australia, that number is upwards of 79% of elected officials.

4% of Biden’s Cabinet is made up of ‘Native American’ people, even though only 1% of their overall population identifies as such. The closest comparison we can draw in Australia is 2% of candidates are Indigenous. This is as compared to 3.3% of Australia’s population.

“Liberal MP, Ken Wyatt and Labor MP Linda Burney are the first indigenous man and woman elected to the House of Representatives and they both sit in the current parliament, but despite their dogged determination and advocacy, the lack of more indigenous representation means the traditional owners of this country barely have a whisper in our national Parliament.”

From The Mckellin Institute Research

There have been recent attempts to address Indigenous inequity in politics earlier this year by offering an Indigenous Voice group in regional and federal government.

In practice, this would involve a body addressing matters of concern to ‘Indigenous Australians’, set up by the current government. In this case, of course, that is the Morisson Liberal coalition.

Being instituted by act of parliament, however, rather than enshrined in constitution means its powers would be uncertain, as would its permanence as it can be disbanded by future coalitions. A government could just as easily disband the group. As such, it has drawn criticism for being tokenistic and potentially meaningless.

It’s definitely a step in the right direction, that this conversation about Indigenous representation is being had. What might be preferable to the proposed Indigenous ‘voice’, is more Indigenous representatives – particularly in those communities with large Aboriginal populations. This, however, is a longer term proposition, and requires a great deal of planning and thought – not a common strength in governments elected term by term.

As Andrew Jakubowicz writes:

“Parliament is essentially a white club, it is essentially a white boys club … The dynamic of change which is sweeping through the Australian community more widely is very apparent at the state level, but the federal level it seems to have been squeezed out,”

The answer may be introducing more quotas – the Australian television program Q&A discussed this issue in detail on their episode on diversity in politics, on the 8th of April 2021. On this episode, in the words of Anika Wells:

“Quotas forces us to look for merit where it has not looked for it before… Talent is everywhere but opportunities aren’t… Quotas give us the diversity which is the strength of a representative democracy.”

Therein, an important point is raised – If the task is for a representative democracy to represent a society and it’s not doing that that then we are failing at the very first hurdle.

Why it matters

The lived experience of racial discrimination and adaptation to our country is important. The voices that tell of the refugee or new migrant journey, or, conversely, the perspectives of Indigenous community members, these are crucial to our national cultural narratives.

As such, the presence of these voices in government and in public discourse are critically important. Who better to represent new Australians and indigenous people than those who have lived the experiences and appreciate the challenges and triumphs associated?

The recurrent theme in my writing and all my work is representation. From the genesis of the organisation I founded, Cultural Infusion, to the new Diversity Atlas – a world-first tool for mapping diversity currently being used by multinationals to map their global workforce – representation is important.

This isn’t just the morally right way to be – in my opinion, it is, but there’s more than social justice at stake. It’s good for our GDP as well – in the corporate and business world, companies who ‘do diversity better’ find improved profits and better staff retention. Why do we think it should be different for governments?

What’s more – if diversity is good for Australia, why do our leaders seem to think this does not extend to them as a body? If we better understood the cultural diversity in all its richness, beyond the white anglo then that could be a way to look at the broader levels of diversity that does exist in our country. This will indubitably help the conversation progress, and lead to the action we need.

If we want to be “the most successful multicultural country in the world”, as our political leaders would have it, it isn’t enough to talk. We also need to listen. We need to act.

Share this Post