Ever thought some of our systems are dehumanising? Democratised datasets are essential to creating human-centred systems that recognise the complexity and interplay of human identity.

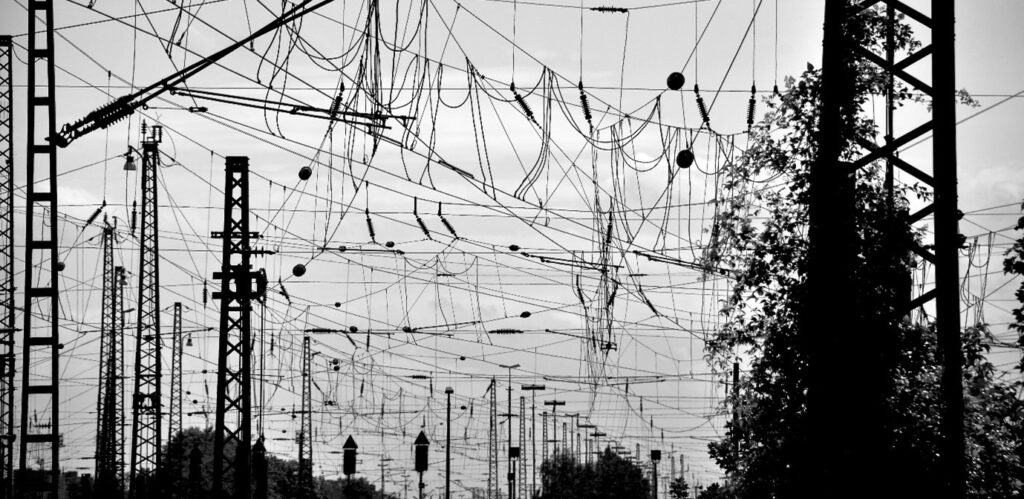

Our contemporary human world is constrained within a system of intricate, manipulable patterns and distorted shapes that run through our networks like a tangle of old powerlines, because of the outdated, hierarchical datasets that are pervasively used in every field – when we could be making a collective shift to democratised datasets.

Nothing is more political than the datasets chosen to gather information on populaces, so why does current social and political discourse largely ignore them? There seems to be a Grand Canyon sized knowledge gap between the fields of data science and sociology, and the general public are stranded somewhere in this chasm of ignorance.

What Are Datasets?

Datasets are collections of related data. For instance, you may want to research a car to buy. You know you want a four-door hatchback, so you compile a list of all the four-door hatchbacks on the market so you can compare their features by collecting relevant data on each model. Your list of four-door hatchbacks is a dataset.

As cultural theorist Stuart Hall pointed out several decades ago, humans make sense of the world by creating categories. Datasets are a form of categorisation, which means they are a powerful meaning-making tool. Every time we use a label like POC, WOC, LGBTQ’, ‘black’, ‘white’ and ‘Indigenous’, we are referring to a category – a dataset – of people. Each of these homogenising labels represents a politicisation (or counter-politicisation) of identity that elide important distinctions between people within these groups.

These broad categories often help empower marginalised people through collective advocacy but they also often lead to offensive stereotypes, polarisation, othering and social division. As historian Patrick Wolfe wrote in his 2016 book Traces of History: Elementary Structures of Race, ‘Paradoxical as it may seem, to homogenise is to divide.’

Being coded black, white, Aboriginal, Asian, African, European, disabled, LGBTQ, male or female can for some people mean feeling put in a homogenising box that they had no say over and for others can mean policing the box’s borders (from within or without) with extreme vigilance, including violence.

What Are Democratised Datasets?

So much depends on holistic data. (Note that I am using the terms democratised data and holistic data interchangeably.)

Democratised datasets are all inclusive. By this, I mean they do not force people into oversized boxes by giving them no option but to choose broad identity labels for themselves or tick a box called ‘other’ when filling out surveys such as their national census, but allow people to identify their specific cultural attributes, down to the dialect they speak and the specific cultural groups and specific worldviews or religions and sub-branches of religions they identify with.

A democratised language dataset, for instance, is a dataset populated with every known language, dialect and speech group. The resulting information gives organisations a full understanding of who they are and allows them to proceed with greater self-awareness and effectiveness.

We now have the technological capacity to use democratised datasets. This is what anyone who wants a more harmonious, equitable and peaceful world ought to be loudly advocating for.

“But Peter, why can’t people just type in their cultural attributes? What is the point of datasets?” These are questions I field quite often.

If you were managing a small team, it would be easy to collect the data and sort through them manually, but once a group numbers over about 20 people, the task becomes more laborious. For extremely large groups, it would be almost impossible. In our increasingly complex globalised world, we need the assistance of machines.

Datasets allow our analytics tool, Diversity Atlas, to instantly sort the data gathered from completed voluntary self-identification surveys. It then displays the highly meaningful results, such as which languages are spoken and which religions are followed within a group. This is a highly efficient method for determining the cultural composition of an organisation. It is also the most ethical way to gather diversity data, because, importantly, the information is de-identified and anonymous. This means no one, not even the software tool, has access to any individual’s personal data. The anonymity, privacy and security features of Diversity Atlas encourage high levels of trust, disclosure and engagement.

How amazing that there is such a thing as ethical technology!

Democracy is in the detail.

Conjuring Indra’s Net

On any given day, a lot of ideas float through my head. The idea of Indra’s net was a concept that took root, forming part of the inspiration behind Diversity Atlas.

In Eastern philosophy, Indra’s net is a concept that symbolises the interdependence and interconnectedness of everything in the Universe. It is described as an infinite net that stretches across eternity, with a multifaceted jewel at the centre of each intersection that reflects every other jewel. As a model, Indra’s net is congruent with the theory of quantum mechanics, and illustrates the concepts of sunyata (Sanskrit word for emptiness: all things lack inherent existence and are instead defined by their relationships and interactions with other things), pratityasamutpada (Sanskrit word for dependent origination: all things originate from a multitude of sources in response to a multitude of conditions) and ananyatva (Sanskrit word for interpenetration or mutual identity: there is no separate existence; we exist because of each other).

We can use the model of Indra’s net to visualise UNESCO’s 2005 Convention on the Protection and Promotion of the Diversity of Cultural Expressions. As its third principle the Convention asserts that the ‘protection and promotion of the diversity of cultural expressions presuppose the recognition of equal dignity of and respect for all cultures [my emphasis and raison d’être], including the cultures of persons belonging to minorities and indigenous peoples.’

Today, through technology, we can conjure Indra’s net and honour these guiding principles. There is a pressing need for us to do this in our globalised world, where increasingly diverse societies need to satisfactorily manage their diversity. As author Richard Powers said in an interview with the LA Review of Books, ‘Life [today] is simply too complex and interdependent for us to wrap our heads around without the help of our machine prosthetics.’

The Distorted Field of Hierarchical Datasets

The Ebbinghaus Illusion, represented in the above diagram, exemplifies how perception operates within a relational field: both blue circles are the same size, yet the one on the right seems larger to most people due to the surrounding context. This isn’t just an optical trick but illustrates how our brains process information relationally. Just as Indra’s net suggests, we only make sense of things in relation to other things.

I tell people the Diversity Atlas platform ‘doesn’t take a position’. By this I mean Diversity Atlas doesn’t take a subjective human position. Its datasets are grounded in the supposition that all cultures (and by extension all humans) have equal value, as per the UNESCO 2005 Convention’s third principle, and Indra’s net.

As living humans, not all cultures have equal value to you or to me, because we live in a relational field and the cultures we’re in closest contact with usually have the most value to us. It would probably benefit me to learn Icelandic, but I doubt I will ever do this. On a subjective level, at this point in my life I simply don’t value Icelandic as highly as I value English, which allows me to communicate with ease with most people and organisations that I am currently in relationship with, or Greek, which is my mother tongue. (My desire to learn Icelandic will strengthen if Diversity Atlas starts extravagantly flourishing in Iceland and I begin spending time there.)

Regardless of my subjective position, when it comes to looking at data, I want Icelandic to be on an equal footing with English and Greek. This allows me to make my choices from a balanced perspective.

For a talk I delivered earlier this year at Big Data & AI World London, my research team found a paper published by Meta titled ‘A diverse, large benchmark for measuring fairness and robustness in audio/vision/speech models’. In this paper, which has since been replaced by an updated version, the authors wrote, ‘The seven race groups used are White, Black, Indian, East Indian, Southeast Asian, Middle East, and Latino, and the dataset is reasonably balanced across these groups.’

Racial categories are simplified, broad categories that group together individuals with vastly different backgrounds. Just as our brains tend to misinterpret the relative size of circles based on their context, racial categorisations lead us to overestimate similarities within groups and overlook the differences.

When we rely on simplified categories, we reinforce a perception that each group is equally represented and equally understood. However, just as the Ebbinghaus Illusion warps our perception of size, oversimplified categories in datasets create a distorted understanding of diversity.

A democratised dataset is genuinely balanced, recognising the spectrum within each of these groups. For instance, when ‘Middle East’ is broken down into more meaningful subcategories, we see Egypt as distinct from Israel or Iran.

The point I am making here is subtle. Look at the Ebbinghaus illusion again or any other optical illusion and reflect on how your understanding of the world is formed. My point is:

We are not even aware of how distorted our ideas about culture are, shaped by the skewed datasets that inform most organisations, including government bodies.

Just as an experiment, ask yourself and the people round you how many Anglo-Celtic languages there are before looking up the answer. Do native Welsh speakers enjoy the same level of privilege as a native standard-English speaker? What are the effects of categorising Czech people with Spanish as Europeans or Thais with Vietnamese as Southeast Asians when these nations have such vastly different histories and cultures?

Remember: we make sense of things in relation to other things.

The damaging ways the ‘model minority’ stereotype plays out for many Asians in the diaspora has been widely written about, as per Viet Thanh Nguyen in Time: ‘Unlike the engineers and doctors who mostly came from Hong Kong, Taiwan, China and India–the model minority in the American imagination–many Hmong refugees arrived from a rural life in Laos devastated by war.’ Nguyen quotes Christian minister Ashley Gaozong Bauer of Hmong descent: ‘When have Asian Americans shared in the pain and suffering of the Hmong refugee narrative and threats of deportation?’

How do we get everyone to feel valued for who they really are?

Hierarchical Datasets Are Still the Standard

Astonishingly, almost no one seems aware that we can shift from selective to democratised databases. Selective datasets are hierarchical and create selective insights, yet in 2024 they are the standard across every industry and government body in the world.

The field is changing, and by 2032 the big data analytics industry is predicted to grow from US$400 billion to US$1.2 trillion, raising its worth to above 1% of global Gross Domestic Product. How much of this growth will be ethical and holistic?

Why Are Datasets for Flowering Plants Better than Datasets for Humans?

When people identify with broad groups it is often to empower themselves. For some people this may be necessary for survival within hegemonic systems and is a valid strategy. But in 2024 leaders in the public and private sectors have the capacity and surely the responsibility and self-interest to use comprehensive datasets structured to reflect the deeper diversity of who we collectively are.

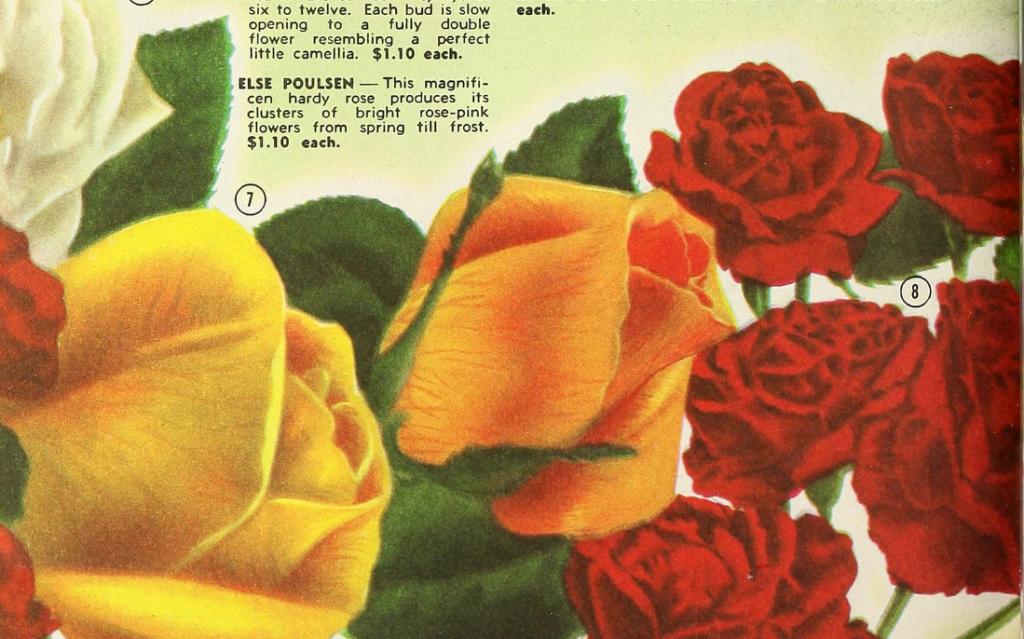

Limited datasets create degraded data, which lead to poor policy just as degraded soil leads to poor quality flowers. Poor policy can and does destroy people and cultures. Just as we collectively misuse and take our soil for granted, we also misuse and overlook the importance of data, which is apparently not glamorous enough to get the attention it warrants.

We would be taken aback if we couldn’t identify the popular variety of rose we want from a plant nursery’s catalogue because all rose varieties were bucketed into a broad category ‘flowering plants’ without further detail. Why do we put up with this level of homogenisation for human varieties?

Nothing is more significant than datasets in terms of shaping policy. Democratised datasets that include every known category of cultural background represent a quantum shift from selective, hierarchical datasets in terms of the quality of data they produce.

We should be taking to the streets with placards demanding democratised datasets.

The technological capacity now exists to shift to holistic datasets that contain every known variable of human culture, identity, appearance and activity, and this shift can be global. Do we have the imaginative, empathetic and moral capacity and will to make this switch?

Share this Post