Machine intelligence can unlock enormous value for organisations and the communities they serve. Unlocking diversity in the Age of AI is a new frontier.

I’m known as Peter, however my real name, Panagiotis, is the name that appears on my birth certificate and passport. Why the difference? Because when we were growing up in the ’70s in Australia many of us Anglicised our names, not only because we wanted to be accepted but also because of fear our names would be used against us.

I can say the work I do now I’ve been training for since I was a kid; learning to navigate the social complexities of Australia, which, like the UK, is one of the most culturally diverse nations on earth. Questions that drive my work are: How do we make sure everyone who wants to be included is, and no one is left behind? How do we give visibility to everyone?

In 2002, I founded Cultural Infusion as a response to the impact of globalisation on society, to encourage understanding of the so-called ‘other’ and reduce discrimination.

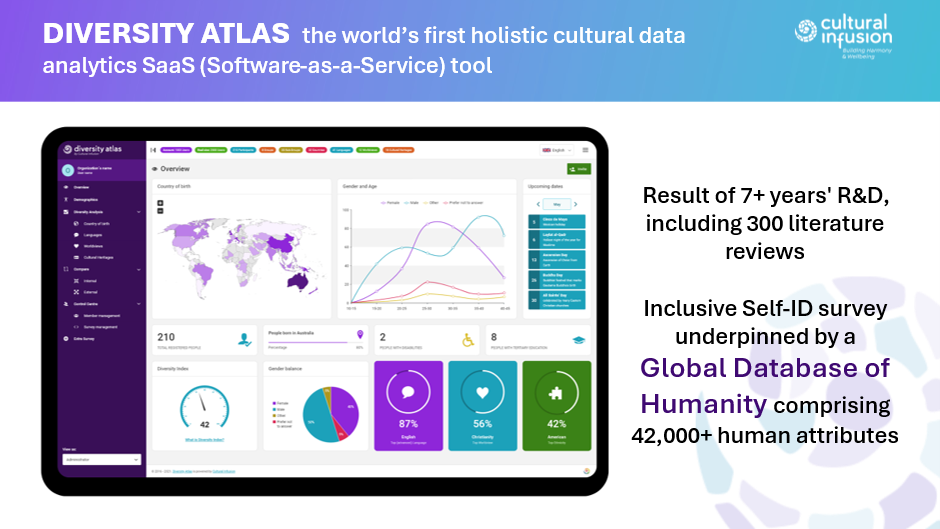

Nearly two decades later, in 2019, I launched the world’s first holistic cultural data knowledge tool, Diversity Atlas, which has been adopted by organisations ranging in size from 50 employees to behemoth companies such as Amazon Web Services (AWS). Diversity Atlas is the culmination of the work and thinking I have been doing around identity, culture and peace in a professional capacity since 1988.

Globalisation has made it a more-than-human challenge to understand ‘the other’. We need the aid of technology. Writer Richard Powers put it this way: ‘Life [today] is simply too complex and interdependent for us to wrap our heads around without the help of our machine prosthetics.’

We’re in the early stages of understanding AI and how to make the most of it. Things are moving so fast that we don’t often get the time to look at aspects of AI that may have massive consequences.

The Cost of Conflict

Culture is a mighty force, a fire that warms and protects but can also burn and destroy. UNESCO identifies culture as:

- a driver of sustainable development;

- an eradicator of poverty;

- key to quality education, and;

- key to building socially cohesive and peaceful communities.

Culture is also a significant enabler of innovation. After all, innovation thrives on the diversification of ideas. What better way to foster innovation than by bringing together the diverse perspectives of different cultures?

So, what is culture?

Well, the term is extremely slippery, and its definition depends on what context and what type of culture we are referring to.

Simply put, culture is the ways in which a particular group of people live. Culture includes shared knowledge, values, customs, physical objects and social norms.

It provides the frames, the contexts, the lenses, through which we all see the world.

I want to stress the important role of culture in any question that affects humanity, especially the development and adoption of any new technology.

What is at stake? According to the Global Peace Index in 2022 alone we spent US$17.5 trillion dealing with conflict. According to UNESCO, about 75% of the world’s conflicts have an ethno-linguistic and religious cultural dimension. This, in 2022, equated to a staggering US$13.1 trillion. This figure is undoubtedly growing.

The big cost is lives, livelihoods and human happiness.

Since culture-based conflict is so prevalent, then why are we not putting culture at the heart of all technological development?

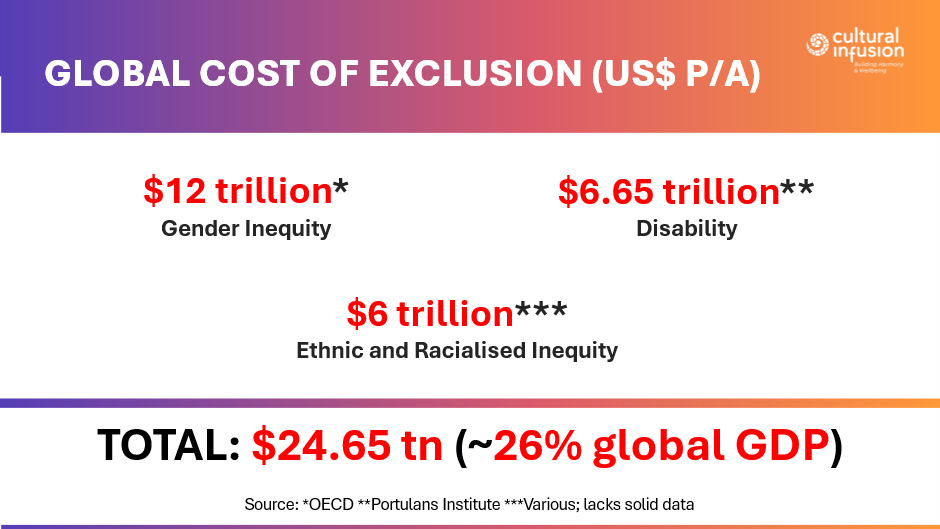

The Global Cost of Exclusion

How about other areas of culture and human diversity, like how we see gender and disability – isn’t this also cultural?

Widespread exclusion from opportunities to participate in society has a huge social, ethical and political cost. How many people realise that how we relate and behave towards each other also has a measurable dollar cost? Exclusion, or even just the perception of exclusion, may cause certain groups to opt out of markets, services and spaces.

It is estimated that nations lose up to 7 percent of their Gross Domestic Product (GDP) due to the exclusion of persons with disabilities.

Globally, the loss in human capital wealth due to gender inequality alone is estimated at $12 trillion per annum.

Based on national estimates from the US and Australia, the figure for ethnic and racialised exclusion is probably similar to the figure for disability but there’s a glaring lack of available data, which is in itself a manifestation of this significant problem.

Look at this total figure representing the global cost of exclusion – US$24.65 trillion a year, which doesn’t even factor in many other forms of discrimination based on religion, sexuality, age, caste, class, appearance and more.

We must centre cultural diversity, equity and inclusion in our conversations about new technology if we’re to avoid perpetuating harm.

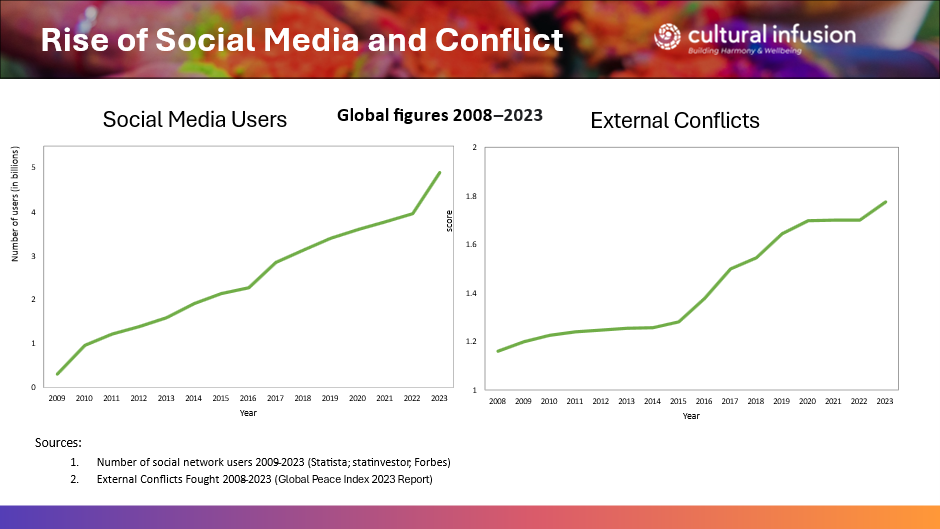

The Rise of Social Media and Conflict

Social media, which started making a big impact in around 2005, gave underrepresented people a much more significant voice in the public sphere. Think back to the Arab Spring in 2011 and how it was fuelled by social media.

Think also of the shaming, naming and blaming we witness on social media, leading to heightened polarisation and conflict. Governments failed to adequately address these destructive aspects of social media. This graph, before you, shows a striking correlation between growth of numbers of people using social media and external conflicts.

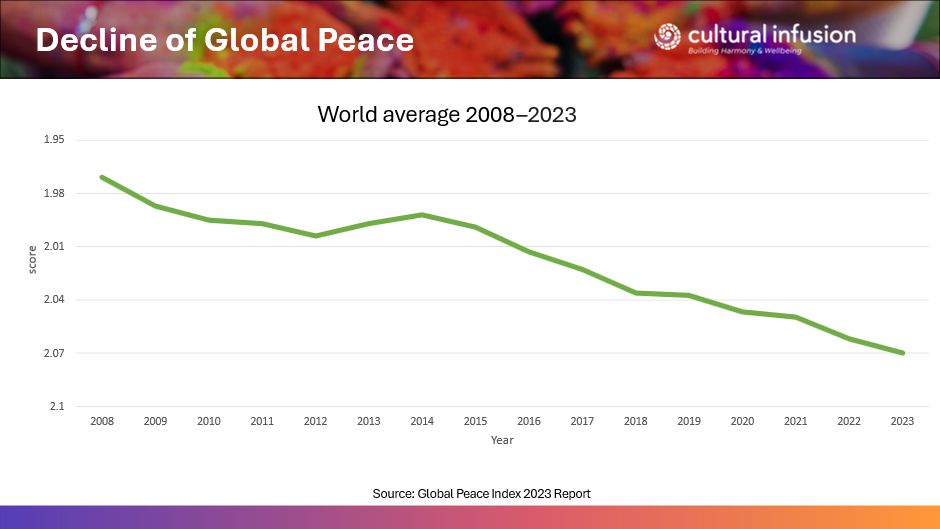

The Decline of Global Peace

Here, in the same timeframe, we see the steady decline of global peace.

Is it any coincidence?

Like social media, AI promises a multitude of social benefits. But AI is only as good as its developers and users and the policies in place to guide it.

If we’re collectively careless with AI, its rise could be accompanied by a corresponding increase in exclusion, poverty, unequal health outcomes and conflict.

A Rapidly Accelerating Journey

Humans are immensely adaptable. Our species can live in more variable environments than any other animal (with the possible exception of tardigrades, also known as ‘little water bears’ or ‘moss piglets’).

The reality is that the Human Race has been on a phenomenal, rapidly accelerating journey in the last 10,000 years.

From 100,000BC to 10,000BC the global human population remained relatively stable at about 1 million (though some estimates are as high as 15 million).

It took us about 10,000 years to reach 1 billion people in 1804.

It took another 123 years for the human population to double to 2 billion in 1927.

We became 3 billion in 1960.

4 billion in 1974.

5 billion in 1987.

In 2022 we became 8 billion.

In less than 100 years we’ve quadrupled.

In 1989, the tearing down of the Berlin Wall was described by political scientist Francis Fukuyama as the end of history as we knew it. The bringing down of barriers. This same year Tim Berners-Lee gifted us the World Wide Web. Within three decades, the world experienced massive economic globalisation without matching globalisation of values and ethics. Today, with the near ubiquity of the internet we are finding ourselves in a super-diverse world where time and space have been compressed. Peace has been on a steady decline since.

More than 65% of the world’s population has internet access.

Meta (formerly known as Facebook) launched in 2004 (as The Facebook) and now has more than 3 billion active users – nearly 56% of all internet users.

The large language model ChatGPT attracted a million users in just 5 days after going public on 30 November 2022. It now has more than 180 million users.

This indicates the phenomenal speed and change we’re experiencing.

Humanity can be defined by an ongoing flux of migration and conflict. My grandparents were banished 101 years ago from the Ottoman Empire, from the area today known as Türkiye, and my parents in the bottom right migrated to Australia in the ’50s for a better life. Who among us cannot be defined by a journey?

AI is a logical extension of human adaptability and sharing and quest for speed and knowledge. Can it solve the challenges of globalisation: the intercultural misunderstandings and exclusions that are costing us so much in terms of human happiness and dollars? Or will it, unchecked, exacerbate current conflicts and inequities?

The ability to understand and relate to the other is now more important than ever.

Diversity Atlas and the Global Database of Humanity

I am using Diversity Atlas to explain a concept that I think is extremely important when it comes to developing and using new technology. Diversity Atlas is underpinned by the Global Database of Humanity, which comprises more than 42,000 human attributes, including every known language and dialect, secular and non-secular tradition, ethnic group and country of birth, gender, age, sexual orientation, sex at birth, position level, position type and many other dimensions, which can shed light on the correlation between experience and identity like never before.

Importantly, Diversity Atlas avoids lazy, outdated racial categories to allow people to gain a clear view of where inequities are playing out in any given context – which may or may not be along ethnic, religious and/or appearance lines. In other words, we don’t group people into broad, unnuanced categories like ‘African’, ‘Asian’, ‘White’ or ‘Black’.

Broad categories of one kind or another were once necessary for people in leadership roles because they had to rely on humans to count groups of people and sort them into categories with assigned meanings. Now that we have machines to do this work there is no excuse to take this crude approach.

The granular insights from Diversity Atlas help organisations identify stakeholders, shape Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI) strategies and inform business goals by effectively leveraging the skills and knowledge of their people. It sheds light on organisational identity by answering the question, Who are we? Our work relies on AI working in combination with data scientists and cultural experts to process the vast amounts of intersectional data our analytics tool generates.

AI can assist with identifying patterns, however it cannot replace the humans whose job it is to understand the information a particular organisation needs. This work requires the experience of living as a human in the real world and the sort of intuition, compassion, creativity and critical thinking that comes from that. Even Pi.AI told me that.

The Complexity of Human Identity

Human identity is complex because humans are multifaceted. As with a Rubik’s cube, it is not a successful outcome if we ‘solve’ one aspect of identity and leave the rest in disorder. Our challenges require a holistic approach. We need to factor in all attributes, not only gender, disability or racialised attributes but simultaneously all relevant identity markers if we’re to avoid the pushback and myriad unintended consequences of doing this work selectively. Gender, for example, is important but it is no more important than other human attributes when considering who gets left out or treated as lesser.

What Is Data?

Data on their own are meaningless. They need to be sorted into categories (datasets) to enable us to identify meaningful information.

Most organisations that collect diversity data – and I’m thinking of everything from government censuses to DEI and C-suite managers – use extremely selective datasets that are often based on outdated categories, the most obvious one being ‘race’, which is often implicitly touted as a biological fact.

The concept of ‘race’ lost scientific credibility a long time ago. When discrimination occurs against a racialised person there are identifiable and measurable characteristics behind that, which could be: ethnicity, caste, religion, and/or appearance, or even language.

We need holistic data to find out what is going on.

Selective datasets lead to selective information and people jumping to incorrect conclusions.

We need the most granular data possible because…

We Don’t Know What We Don’t Know

When we are missing a lot of data, our minds are quick to make assumptions to fill the gap.

What assumptions have you already made about the people in this room? I guarantee that if we ran Diversity Atlas with this group, you would be astonished by the hidden diversity.

It’s unwise to assume anything by someone’s appearance. The old people knew this when they said, ‘You can’t judge a book by its cover.’

We need to get under the covers to do this work.

Looking Under the Covers at Meta

I looked under the covers at Meta.

This is a paper they published titled ‘A diverse, large benchmark for measuring fairness and robustness in audio/vision/speech models’.

In this paper they write, ‘The seven race groups used are White, Black, Indian, East Indian, Southeast Asian, Middle East, and Latino, and the dataset is reasonably balanced across these groups. However, race is seen as a social construct and its use in categorization exercises may be problematic.’

Say no more!

We need nuanced data that goes beyond appearance and nation states and broad geographic boundaries to define one’s culture and consider other areas of identity.

What would someone from a Kurdish background in Türkiye have in common with a Cantonese person from Southern China? A lot, but there is great dissimilarity, too. How can AI account for these nuances?

If we’re categorised into broad groups, AI will persist in making decisions under the assumption that everyone within these groups occupies the same social and cultural standpoint.

What’s Essential Is Invisible to the Eye

The mass of all stored information on the internet has been calculated as equivalent to one small apple.

In 2007, it was equated to the mass of a strawberry.

I’ve been talking about the value of data but this shows how relatively ‘unmassly’ all our data is.

What’s essential is invisible to the eye and so far cannot be measured in 1s and 0s. I am interested in the spaces in between the data points, because that’s where everything happens.

How do we ensure that AI assists us on a healthy path towards greater understanding, compassion and joy and not more conflict, polarisation and misery?

Confluence is the lifeblood of culture and AI is a powerful expression of confluence.

If the development of AI is in the tight grip of a powerful few who can attract the necessary funding, IT IS LIKELY we will see stagnation in parts of the AI field. This could manifest as increased conflict and polarisation, accompanied by a collective sense of hopelessness, inertia, and a feeling of history repeating itself.

The alternative is learning from our past.

Diversity in the Age of AI: The future lies in the past

“Diversified we grow” is a slogan I coined for a United Nations campaign in 2013. When I coined the phrase I wasn’t just thinking about social cohesion but rather the value that comes with diversity and how it has been a driver for innovation throughout the centuries that can solve challenges.

While embracing AI as another form of diversity, I worry that it will harm people from underrepresented cultural and social backgrounds through erasure or ignorance and that it will harm their cultures.

Cultural diversity is humanity’s greatest asset, as important to sustaining humanity as biodiversity is for sustaining the environment. No culture has more inherent value than another, and this is irrefutable unless you hold supremacist views of some kind. Vast troves of human knowledge are encoded in each specific culture. We need to cherish these diverse expressions of humanity.

If AI is our collective future then we need more AI platforms, made by more people from more backgrounds, reflecting the diversity of our world.

How Do We Mindfully Benefit from AI?

AI is rapidly creating breakthroughs, as in the medical field with AlphaFold, developed by Google’s DeepMind, which almost every pharmaceutical industry is now using.

In terms of DEI, AI has improved accessibility for people with disabilities through speech recognition, text-to-speech and visual recognition. AI is also helpful for bridging communication gaps between different language speakers. ChatGPT 4, for instance, can communicate in more than 50 languages. Thanks to AI, barriers are tumbling down that may have once prevented employers from using someone’s skills.

I often use the new chatbots to help me communicate my ideas. They are like new members of staff. Each of the language models, ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini and Pi, for instance, have different strengths, weaknesses and capacities, because they’ve each been shaped by different data inputs – just like real people but a lot better read, faster and may I add ever so slightly prone to hallucinating. AI chatbots can assist but can’t replace real humans because AI cannot reproduce the emotional depth, personal experiences and unique perspectives that humans bring to their work.

No company today can afford to think AI will compensate for a representatively diverse workforce or that AI is somehow free of bias and erasures. All the big AI developers in the Anglosphere have been criticised for bias, sometimes from within their own organisations. Even though the most recent iteration of ChatGPT has the capacity to communicate in 50 languages, it still excludes thousands of other languages representing value-based systems from across the globe. This is not a holistic system.

Female-founded AI startups currently receive only 2% of funding deals in the UK and US. Ada Lovelace was arguably the first ever computer programmer. Is this field less equitable for women than it was nearly 200 years ago? Who else is missing out on funding deals? Their absence as developers deprives the AI field of much-needed diversity and creates a lot of questions in my mind.

There’s never been a more important time to advocate for genuine representation in the technology industry. An equitable allocation of funding would lead to a more vibrant, less biased and more human future for AI.

If we have diversity in tech, we have healthy tech.

My final word is a call to work together, tread carefully and recognise the importance of every voice moving forward with AI.

The content in this post was based on the keynote ‘Diversified We Grow: Unlocking Diversity in the Age of AI’ delivered at Big Data & AI World, London, March 2024

Share this Post